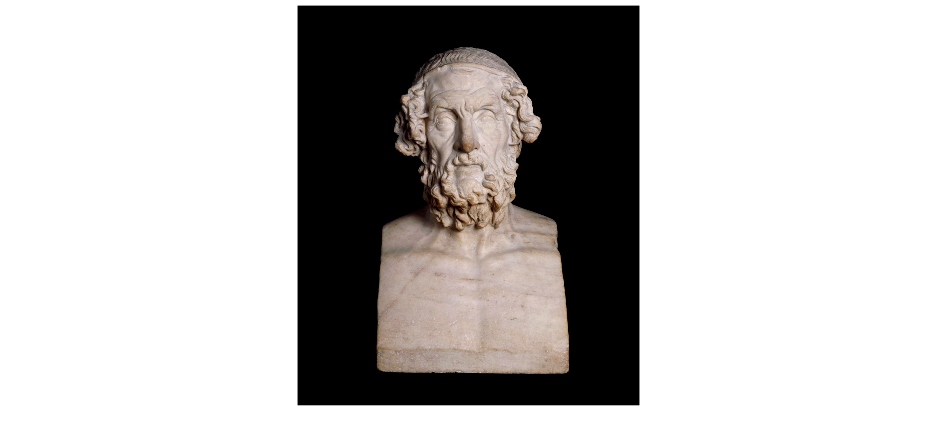

Homer speaks today: What we can Learn from Homer About War.

- liamnaddell

- Nov 26, 2020

- 7 min read

Something that is at the same time frustrating and horrifying has recently reared its head: The idea that the U.S. should shoot first, and use diplomacy later. President Trump's foreign policy defines this. During his tenure he threw out the Iran nuclear deal, imposed new sanctions, and assassinated one of their generals, all in line with his being "the most militaristic person." While most voted against Trump, some Americans see something beneficial in Trump's aggressive, militaristic policy. I personally believe this militarism is incredibly damaging to our society, and to see why, let's look at some themes related to war in the Homeric epics as well as how they compare to today's beliefs about war; themes like glory, the reason for fighting, and the presentation of warfare, ending by looking at how the modern conception of war changed from Homer to the present. Hopefully, by looking at the history and historiography of war, we can understand its true nature.

It would be immensly difficult to discuss the separate opinions of hundreds of millions, so we must first pin down what the modern conception of war is. Many credit WWI as the war that defines the modern view. Haley E. Claxton, writing for Crossing Borders, says, "War was not a glorious spectacle with glittering swords and shining armor in which dragons were slain and damsels in distress were saved. Instead, it was hell on Earth. This realization would forever leave an impact on those who had lived through the Great War."1 The book that arguably codifies this realization the best is Erich Maria Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front. For that reason, I will use the book as the basis for the modern conception of war. Through Paul Bäumer's eyes as an average German trench-warfare soldier, we see the devastating effects of

1. Claxton, "Knights of the Front," 11.

WWI. Far from a noble struggle, war is likened to a mass slaughterhouse from hell: War is attritional, it destroys the mental state of the soldiers, and it is masterminded by a group of self-interested and abusive leaders. In total, war is hell.

The first spot of agreement between Homer and a modern readeris in the presentation of the horrors of war.The Iliad's endless fight scenes, dust-biting, and nipple-piercing, emphasize how long, attritional, grueling, and gruesome Homeric war is:

The henchmen of Idomeneus stripped the armor from Phaistos,

while Menelaos son of Atreus killed with the sharp spear

Strophios' son, a man of wisdom in the chase, Skamandrios,

the fine huntsman of beasts. Artemis herself had taught him

to strike down every wild thing that grows in the mountain forest.

Yet Artemis of the showering arrows could not now help him,

no, nor the long spearcasts in which he had been pre-eminent,

but Menelaos the spear-famed, son of Atreus, stabbed him,

as he fled away before him, in the back with a spear thrust

between the shoulders and driven through to the chest beyond it,

He dropped forward on his face and his armor clattered upon him.

Meriones in turn killed Phereklos, son of Harmonides,

the smith, who understood how to make with his hand all intricate

things, since above all others Pallas Athene had loved him(Homer, Iliad.5.49-61, trans. Richard Lattimore).

All Quiet on the Western Front emphasizes the same themes, albeit to a far greater degree: "We recognize the smooth distorted faces, the helmets; they are French. They have already suffered heavily when they reach the remnants of the barbed wire entanglements. A whole line has gone down before our machine-guns; then we have a lot of stoppages and they come nearer. I see one of them, his face upturned, fall into a wire cradle. His body collapses, his hands remain suspended as though he were praying. Then his body drops clean away and only his hands with the stumps of his arms, shot off, now hang in the wire."1 In essence, both books emphasize the horrors of war, just to different degrees.

1. Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front, 112.

For fighting to be this grim, the soldiers must have some kind of inspiring war-goal like the protection of hearth and home! Instead, Homer presents a meaningless Casus belli as part of the deeply unpleasant view of the Trojan War, as a conflict that rages on in spite of its relative pointlessness.On the Trojan side, Hektor harangues Paris, blaming him for the war, saying "Evil Paris, beautiful, woman-crazy, cajoling, better had you never been born, or killed unwedded. Truly I could have wished it so; it would be far better than to have you with us to our shame."1Hektor sees nothing of value in this war and he wishes it away. If he could snap his fingers and stop the fighting, he would. While the Trojans are arguably fighting for hearth and home, in the Greeks we see a much darker reason for warfare. Near the beginning of the Iliad, we witness the Greeks ready to set sail for home and abandon the siege. For them, proudest of men, the losses are just too high to fight for one man's dignity. However, the Gods have conspired against them, and told Odysseus to continue the fight because "would you thus leave to Priam and to the Trojans Helen of Argos, to glory over, for whose sake many Achaians lost their lives in Troy far from their native country?"2 This is a presentation of the Gambler's Fallacy at its peak. This justification, which eventually holds sway among the Greeks, boils down to continuing the war because otherwise the sacrifices we made would be in vain. This logic reveals the real Casus Belli nine years in: "We are at war, because we are at war, not because we wish to remedy, solve or punish any offense."This encounter shows that in war it is important to know when to cease-fire and that it is never beneficial to justify the continuation of war by the previous casualties.

While The Iliad mentions glory often, inAll Quiet on the Western Front, we never see one mention of glory or chivalry. The book even opens by saying that war is not an adventure.3

1. Homer, The Iliad, trans. Richard Lattimore, 118.

2. Ibid, 97.

3. Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front, 1.

Becky Little, writing for history.com would agree, saying, "But after the horrors of World War I, the notion of “chivalry” lost its luster as returning soldiers became disillusioned with the idea that there can be any glory in war."1 While All Quietcompletely rejects glory, Homer confronts it regularly. Hardly ten pages go by without some character referencing glory, either to be won or lost. In the end though, Achilleus, the one arguably most harmed on the Greek side by the Trojan War, skewers this notion in his post-mortum conversation with Odysseus, saying "I would rather follow the plow as a thrall to anotherman, one with no land allotted him and not much to live on,than be a king over all the perished dead."2 Achilleus, who gained eternal glory in death, first among the Greeks, writes he would give it all away in favor of being the slave of a landless man, the lowest of the low. To me, it seems like Homer would argue that war-glory is not worth the life you lose by dying in battle.

Now that we have a good picture of how the modern conception of war and the Homeric compare, I believe it is important to answer how we got from the Homeric worldview to the modern by looking at some of the historical practices that influence us today. After the Trojan Cycle, the next most influential literary source would be the broad category of chivalric literature popular in the middle ages. These books would often substitute a literal conflict for a moral one. For example, in the Faerie Queene, The Redcrosse Knight fights all kinds of dragons, evil warriors, and snakes which represent his inner temptations. This led to an interesting effect: the global misrememberence of an entire genre. Often times these books could be incredibly intense, so much so that some of them are not fit for reading to children, however, it seems that many remember these books as Mary-Sue-esque knights easily overcoming dragons and saving

1. Little, "How Chivalry Died."

2. Homer, The Odyssey, trans. Richard Lattimore, 180

helpless princesses from towers, which might be a remnant of WWI era propaganda. Per Haley Claxton, "For European nations in particular, chivalry and knighthood are widely regarded as historical concepts of great pride. In the centuries between the Middle Ages and the start of the First World War in 1914, stories of knights, chivalric codes, and other forms of “medieval history” were well recognized and formed “a prism through which the contemporaries viewed the present.”"1 This is apparent in WWI era propaganda, which often display figures like King Arthur, Joan of Arc, or more generic knights winning glory in battle. This imagery fit the needs of the high command in every European nation to motivate men to enlist or comply with the draft. Because it would be difficult to convince anyone that dying to avenge some Austrian prince is a noble struggle, propagandists had to find a new avenue: convincing the populace that the enemy was the inherently evil "dragon" in medieval literature, often with helpless woman in hand, meaning that the most noble and glorious event of your life would be slaying "the dragon" and saving your nation. This literally demonized your opponent, and turned the war from a military conflict into a total war where one step back must not be taken until "the dragon" is slain. However, this image was shattered during WWI, proving to all that your enemies weren't demons or dragons and that killing them wasn't glorious or noble.

In total, we can learn a lot from Homer, not just directly, but by understanding and comparing his impact on the modern conception of war. Directly, he communicates how hellish war is and how to avoid the devastating effects of the Gambler's Fallacy. Homer's epic cycle also acts as a bulwark against those who would wish to demonize the enemy with propaganda. These lessons are especially relevant to today, where the horrors of war increasingly seem like distant memories. If that process runs to completion, a war more calamitous than WWI or WWII might follow. However, I believe that if we as a society understand the true effects of war on the populace, we can avoid such disasters.

1. Claxton, "Knights of the Front," 4.

Bibliography

Homer. The Iliad. Translated by Richard Lattimore. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

2011.

Homer. The Odyssey. Translated by Richard Lattimore. New York: Harper & Row, 1967.

Claxton, Haley E. (2015) "The Knights of the Front: Medieval History’s Influence on Great War Propaganda," Crossing Borders: A Multidisciplinary Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship: Vol. 1: Iss. 1. https://doi.org/10.4148/2373-0978.1008

Remarque, Erich Maria. All Quiet on the Western Front. Translated by Ullstien AG. New York: Random House Publishing, 1982.

Little, Becky. "How Chivalry Died-- Again and Again." Last modified Aug 2018. https://www.history.com/news/how-chivalry-died-again-and-again

Comments