Political Involvement in the Midst of Plagues: the Great Plague of Athens and Covid-19

- taraafsharzadeh7

- Nov 25, 2020

- 8 min read

Although the Great Plague which struck Athens in 430 B.C.E. and the global impact of Covid-19 in 2020 may appear to have little meaningful connection due to the significant temporal distance between the two events, the clear parallel between the political responses to the catastrophic plague implemented by political officials in Athens, and the response of the Canadian Government is clear, as well as important; by examining the strengths and weaknesses of the Ancient Athenian government’s response to the plague in 430 B.C.E., it is possible to further understand the importance of the Canadian Government’s role in protecting its citizens by implementing imposed isolation, enforcing regulations which prevent overcrowding, and raising morale by allowing the leader to address citizens regarding the impact of the virus. This parallel between the Great Plague of Athens and Covid-19 is valuable to consider, as it offers a historical perspective on the influential role of the government in addressing, controlling, and limiting the outbreak and minimizing the disastrous effects on its citizens through government policy, as well as highlighting important lessons that may also be applied to the current virus outbreak.

The Great Plague of 430 B.C.E. - Response of the Ancient Greek Governments

First, it is valuable to consider the impact of political involvement in the Ancient Greek component of this historical parallel; the Great Plague of Athens. The ancient plague of unknown origin, which is believed to have been a form of typhoid fever from isolated bacterial DNA, struck the population of Athens in 430 B.C.E., during the second year of the Peloponnesian war; due to the overcrowding and overcapacity of the city in accordance with the statesman Pericles’s orders to Athenians to crowd inside the Long Walls linking Athens to Piraeus as part of a war strategy against the Spartans, around a third of the population of the city of Athens died from this plague (Pomeroy 234-235).

Thucydides, a historian and general who overcame the illness himself, recorded his observations about the plague in order to inform future generations about the physical characteristics of the disease on individuals, as well as the measures taken to minimize and prevent the spread. Importantly, Thucydides makes note of the influence of the overpopulation due to the displacement of farmers from the countryside to the crowded city as part of Pericles’s war strategy to congregate Athenians inside the city walls against the Spartans. “A factor which made matters much worse than they were already was the removal of people from the country into the city...living as they did during the hot season in badly ventilated huts, they died like flies” (Thucydides 52-53). Highlighting the effect of overcrowding on the disease and its devastating effect on Athenians in the midst of war with the Spartans outside the Long Walls, Thucydides asserts that victims of the plague were weakened in mind and body, and began to fall prey to lawlessness; men refused to fight, neglected temples, and even forwent burying the dead in Athens (Morgan 205). Despite the disastrous effect of the plague and the resulting loss of one-third of the population of Athens, the response of the statesman, Pericles, as well as the Athenian government to the plague in an attempt to curb the spread and raise morale, is crucial to consider.

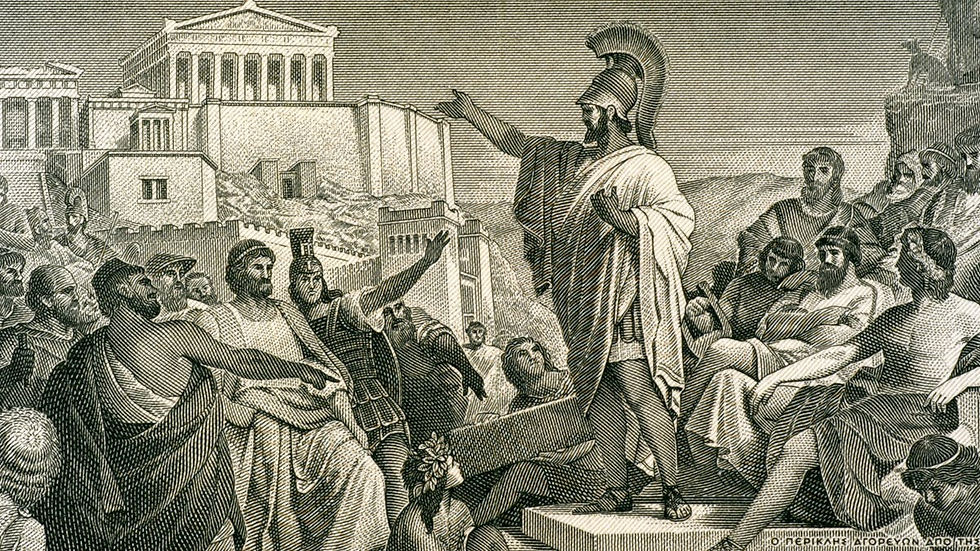

First, in Pericles’s final speech to Athenians ravaged by the plague and the simultaneous war, the statesman quelled fears from the suffering Athenians surrounding the possibility of the plague being an act of divine punishment by the gods; the angry and miserable Athenian citizens believed that this plague was an act by the gods intended to discipline them for the imperial policy that catalyzed the war against the Spartans (Burns 20). Rather than allow the citizens’ worries to fester and cause hysteria, Pericles led a naval expedition in order to redirect the anger of Athenians, and in his final speech before succumbing to the plague himself, expressed that rather than viewing the plague as an act of punishment by the gods, Athenians ought to consider the disease as an event that is unalterable and must be borne out of necessity (Burns 20). In order to offer encouragement to the angry Athenians upset by the perceived error in imperial policy that brought on the wrath of the gods in the form of the plague, the leader encourages citizens to instead look towards the future and anticipate future imperial conquests and glory (Burns 21). In addition, apart from Pericles’s efforts to improve the morale of the Athenians in the midst of plague, the political involvement of the Ancient Greek government in order to minimize the spread of the disease may be clearly seen in the involuntary quarantine which was imposed upon the cities of Potidaea and Plataea (Couch 95).

In addition to stating the impact of crowding and unsanitary conditions which perpetuated the spread of the plague in Athens, the historian Thucydides asserts that citizens died “like sheep” after coming into contact with the infected; this indicates the awareness of the contagious nature of the disease by contemporaries (Thucydides 154). This imposed isolation of two affected cities demonstrates an effort to control the spread of the plague by Ancient Greek governments in cities other than Athens, which was the city most affected by the disease due to the overcrowding within the Long Walls as a war strategy. This imposed isolation provides clear evidence of the Ancient Greek leaders’ cognizance of the efficacy of quarantine through the avoidance of contact with infected outsiders (Couch 95). Strategic military decisions also played a role in the prevention of further contact with the infected. This implementation of government policy reveals that citizens and leaders of Ancient Greek cities were not only aware of the contagious nature of the disease, but also demonstrated an understanding of isolation as a method to prevent further spread of the plague. Although the Great Plague of Athens obviously affected the Athenian citizens most noticeably in terms of the number of the deceased, Spartans also displayed strategic methods to avoid the plague. In 430 B.C.E., Peloponnesians intentionally departed from Attica with great haste after hearing accounts of the plague’s impact from deserters, and witnessing great examples of cremation and death first-hand (Couch 98).

Through the Ancient Greek government’s involvement in the form of speeches by leaders to improve morale, enforced quarantine, and prevention of further spread of the disease by strategic military decisions to avoid contact with the infected, it is clear that the Great Plague which struck Athens in 430 B.C.E was addressed, controlled, and limited through vital action on the part of the government and leaders.

Covid-19 - Response of the Canadian Government

While the outbreak of the Covid-19 virus in in Canada during 2020 may have great temporal distance from the Great Plague of Athens in 430 B.C.E., having thus established the important impact of the Ancient Greek governments’ response to restricting the spread of the plague, it is possible to draw an important historical parallel in terms of the importance of the Canadian Government’s role in addressing the outbreak and protecting its citizens; this is seen in the implementation of similar imposed quarantine, the enforcement of regulations which aid the prevention of the spread of the disease, and the raising of morale of citizens through speeches by the Prime Minister. The global coronavirus outbreak first reached Canada on January 25, 2020; as of November 9, 2020, there have been 268,735 total cases of infection in the country, including 10,564 total deaths (“Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Outbreak update"). First, it is important to note the response of the Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, to the citizens of Canada in response to the growing numbers of cases.

In Ottawa, on March 11, 2020, the Prime Minister outlined a whole-of-government response in the form of a Response Fund of more than $1 billion dollars for the provinces and territories, as well as a public address intended to improve the morale of the country (“Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Outbreak update"). “Our message to Canadians is clear: to every worker and business, in every province and territory, we have your back and we will get through this together" (“Prime Minister Outlines Canada's COVID-19 Response"). An important parallel may be witnessed between the actions of both the Ancient Greek government and Canadian government’s response to the citizens during the outbreaks; the speech of Ancient Athenian statesman Pericles in his address to the weary citizens affected by the Great Plague in 430 B.C.E, and the response of the Canadian Prime Minister to Canadians on March 11, 2020, are both crucial in grounding citizens and providing hope for the country’s flourishment in the future.

A second valuable parallel is highlighted in the travel restrictions ordered in March, as well as the mandatory imposed quarantine orders made by the Canadian Government in June, April, and March 2020, requiring all individuals who entered Canada to isolate for 14 days from the day upon which they entered Canada (“Government of Canada's Response to COVID-19"). This example of the Canadian Government’s action to minimize the spread of Covid-19 through travel restrictions and involuntary quarantine plainly reflects the similar imposed quarantine of the Ancient Greek cities of Potidaea and Plataea during the Great Plague in order to combat unsanitary conditions and overcrowding due to defensive strategies in the midst of the Peloponnesian War. In addition to presenting a clear parallel of isolation to protect citizens from contact with infected individuals, this imposed quarantine presents an example of a lesson being applied from mistakes in the historical element; while the city of Athens suffered from overcrowding which perpetuated the spread of the viral plague, the decision of the Canadian Government to restrict and manage all travellers to Canada and require imposed isolation displays an important improvement and a clear improvement from the government response during the Great Plague.

Through the parallels highlighted in the government’s response to the outbreak of Covid-19 in Canada through monetary assistance to citizens and a public address by the Prime Minister, imposed quarantine, and travel restrictions in order to prevent the spread of the virus from travellers to Canadians, it is evident that the crucial role of the government and its response to the outbreak of disease that is witnessed in Great Plague which struck Athens in 430 B.C.E is similarly applied to the Canadian Government’s treatment of the Covid-19 outbreak in the country.

Conclusion

While it is true that the Great Plague which struck Athens in 430 B.C.E. and the global impact of Covid-19 in 2020 are separated through temporal distance, the important role of government involvement in the response to each outbreak is clear in the responses of political officials in Athens, and the response of the Canadian Government. Through the examination of the strengths and weaknesses of the Ancient Greek government, the importance of the Canadian government’s role in implementing imposed isolation and travel restrictions, enforcing regulations which prevent overcrowding, and addressing citizens in a speech by the Prime Minister is abundantly clear. This parallel offers not only a valuable historical perspective on the importance of the government in addressing the outbreak and minimizing the disastrous effects on its citizens through government policy, but also highlights certain weaknesses of the Ancient Greek response which may be used as lessons when applied to the current virus outbreak.

Works Cited

Burns, Timothy W. "The Problematic Character of Periclean Athens." In On Civic Republicanism: Ancient Lessons for Global Politics, edited by KELLOW GEOFFREY C. and LEDDY NEVEN, 15-40. Toronto; Buffalo; London: University of Toronto Press, 2016. Accessed November 11, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/j.ctt1kk65xt.5.

Couch, Herbert Newell. "Some Political Implications of the Athenian Plague." Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 66 (1935): 92-103. Accessed November 10, 2020. doi:10.2307/283290.

Morgan, Thomas E. "Plague or Poetry? Thucydides on the Epidemic at Athens." Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-) 124 (1994): 197-209. Accessed November 10, 2020. doi:10.2307/284291.

Pomeroy, Sarah B., Burstein, Stanley M., Donlan, Walter, Roberts, Jennifer Tolbert, and David Tandy. A Brief History of Ancient Greece: Politics, Society and Culture. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Translated by Rex Warner. London: Penguin Books, 1972.

Government of Canada, Department of Justice. “Government of Canada's Response to COVID-19.” Government of Canada, Department of Justice, Electronic Communications, Last modified November 9, 2020. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/covid.html.

Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada. “Prime Minister Outlines Canada's COVID-19 Response.” Prime Minister of Canada, Last modified March 11, 2020. https://pm.gc.ca/en/news/news-releases/2020/03/11/prime-minister-outlines-canadas-covid-19-response.

Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada.“Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Outbreak update.” Canada.ca. / Gouvernement du Canada, Last modified November 6, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html.

Comments